Comparing mutual funds, ETFs, and investment trusts: Key differences and benefits explained

Investment funds are all run on the same principles. They pool investments from a range of different investors, providing access to a diversified portfolio that would be difficult for an individual investor to achieve by themselves. However, there are a range of different structures investors can use. Here’s the main three:

1. Mutual fund – also known as an open-ended fund, OEIC or UCITS fund

Mutual funds pool together investors’ money, which is then managed on their behalf by a dedicated investment manager. They will use their skill and experience to choose companies with a strong pathway of growth and/or income, depending on the investment goals set out for the fund. Most mutual funds will have a specific area of focus – say, European stock markets, or the technology sector.

These funds are ‘open-ended’, which means that new units are created when money comes into the fund, and retired when an investor exits. The fund manager will need to buy new investments as new money comes in, and sell investments to meet redemptions. The net asset value of the fund will match exactly the value of the underlying holdings. Mutual funds usually price once a day.

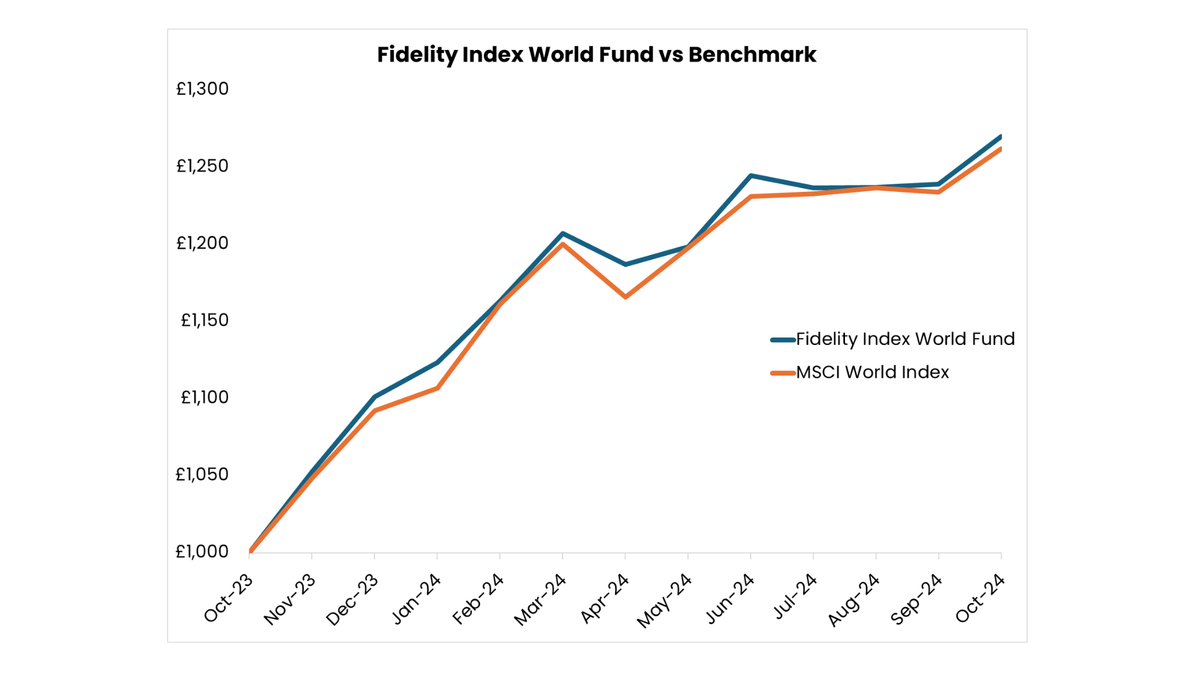

Investors can monitor the performance of their holdings through groups such as Morningstar or Trustnet. Performance is usually judged against their peer group – for a European fund that might be the Investment Association’s Europe ex UK sector, for example – or against a benchmark, so a UK fund might be measured against the FTSE All Share.

2. ETF – or exchange-traded fund

ETFs have some similarities with mutual funds, in that they aim to give cheap, diversified access to stock markets and other securities markets. However, unlike mutual funds, ETFs are traded on an exchange and the price fluctuates according to demand. An ETF can trade at a premium or a discount to the value of the underlying assets (though with large, liquid ETFs, this is rare).

ETFs can be structured to track everything from commodity prices, to major indices, to baskets of stocks. The most popular ETFs track major indices such as the S&P 500 or the MSCI World. The world’s largest ETF – the SPDR S&P Ucits ETF is $18,749m in size[1].

ETFs have multiple options. When investing in stock markets or commodities, for example, they will use ‘physical’ or ‘synthetic’ replication. Physical replication requires buying a small share of each of the underlying securities. ‘Synthetic’ replication aims to create the index or commodity return using derivatives, such as futures.

There are also ETFs on currencies, including more esoteric areas such as Bitcoin and Ethereum. It is also possible to buy leveraged ETFs that offer 2x or 3x exposure to a particular security. There are also inverse ETFs, which use derivatives to go short a stock and – potentially – profit from its decline.

ETFs are usually cheap and liquid. They offer an easy way to get access to a diversified portfolio of companies and investors can buy them easily through a platform or a broker. However, while most people will use them to track a stock market index, they can have a far broader range of uses in a portfolio.

3. Investment Trusts

Investment trusts (or investment companies) are one of the oldest types of collective fund. They are listed companies that invest in shares, bonds, and other assets, such as property. Most commonly, they will invest in a portfolio of shares, but there are also investment trusts that invest in areas as diverse as care homes, wind farms, or aircraft leasing. The choice is vast.

Investment trusts have a board of directors that look after the interests of shareholders. They will ensure the investment manager is staying on track and will take steps to switch if they are not. The board is also responsible for reporting back to shareholders on the trust’s performance.

Investment trusts are ‘closed-ended’, which means that the fund manager doesn’t have to buy and sell assets when investors buy in or sell out of the fund. This gives investment trusts some advantages when managing less liquid assets such as commercial property or infrastructure. Investment trusts can also be useful for income-seekers: they have the ability to reserve income in buoyant times to pay it out in tougher times, helping smooth the return to investors.

The price for an investment trust is determined by the market, so it may trade at a discount or a premium to the value of its underlying holdings. This can give investors an opportunity to buy assets at less than they are worth.

There are good and bad options within all of these fund types and investors can construct a diversified portfolio using just one option, or a blend of all of them. There is abundant choice for all types of investor.

Feature | Mutual Funds | ETFs | Investment Trusts |

Structure | Open-ended; buy/sell shares through the fund | Bought/sold on stock exchanges | Closed-ended; trades like a company on exchanges |

Pricing | Price set once daily | Price changes throughout the day | Price changes based on market (can be above/below value) |

Management | Actively managed by professionals | Typically follows an index (passive management) | Managed by a board that hires fund managers |

Liquidity | Depends on the assets it holds | Very liquid; easy to buy and sell | Can invest in less liquid assets, making it more flexible |

Typical Focus | Specific sectors or markets | Commonly tracks specific indices (e.g., S&P 500) | Invests in a variety of assets (stocks, bonds, real estate) |

Unique Advantage | Managed by professionals who pick investments | Low cost and easily traded on exchanges | Can save reserves to maintain income stability |

Price Determination | Based on total value of holdings (NAV) | Based on supply and demand in the market | Can be bought/sold at prices above or below actual value |

Best For | Investors wanting active, professional management | Investors wanting low-cost, simple access to markets | Investors who want potentially flexible, varied investments |

---